After a first week in which many economies across the globe have come to a halt, most of us realise that at least for the near but potentially distant future things will be different.

While the heroes of the health care system are working relentlessly to treat the infected and stop the illness COVID-19 from spreading, many have set up their home offices, and maybe this is the right time to rethink your business, research, and beliefs. Now that individuals are self-isolating, businesses are closed, and in many countries, a state of emergency is officially declared, the issue of climate change that had dominated most of last year’s headlines has virtually vanished from the news. It is now more important than ever not to forget the Sustainable Development Goals. The SDGs have not been postponed and stopping climate change is arguably the single biggest modern challenge humans face. If we do not decouple economic growth from the consumption of virgin non-renewable resources, there will be no habitable planet left for the generations following those saved today from the coronavirus. Whether you are a manager, researcher, or employee, the past days may have already set you thinking and confirmed or challenged your beliefs about your business model, operations, or research assumptions.

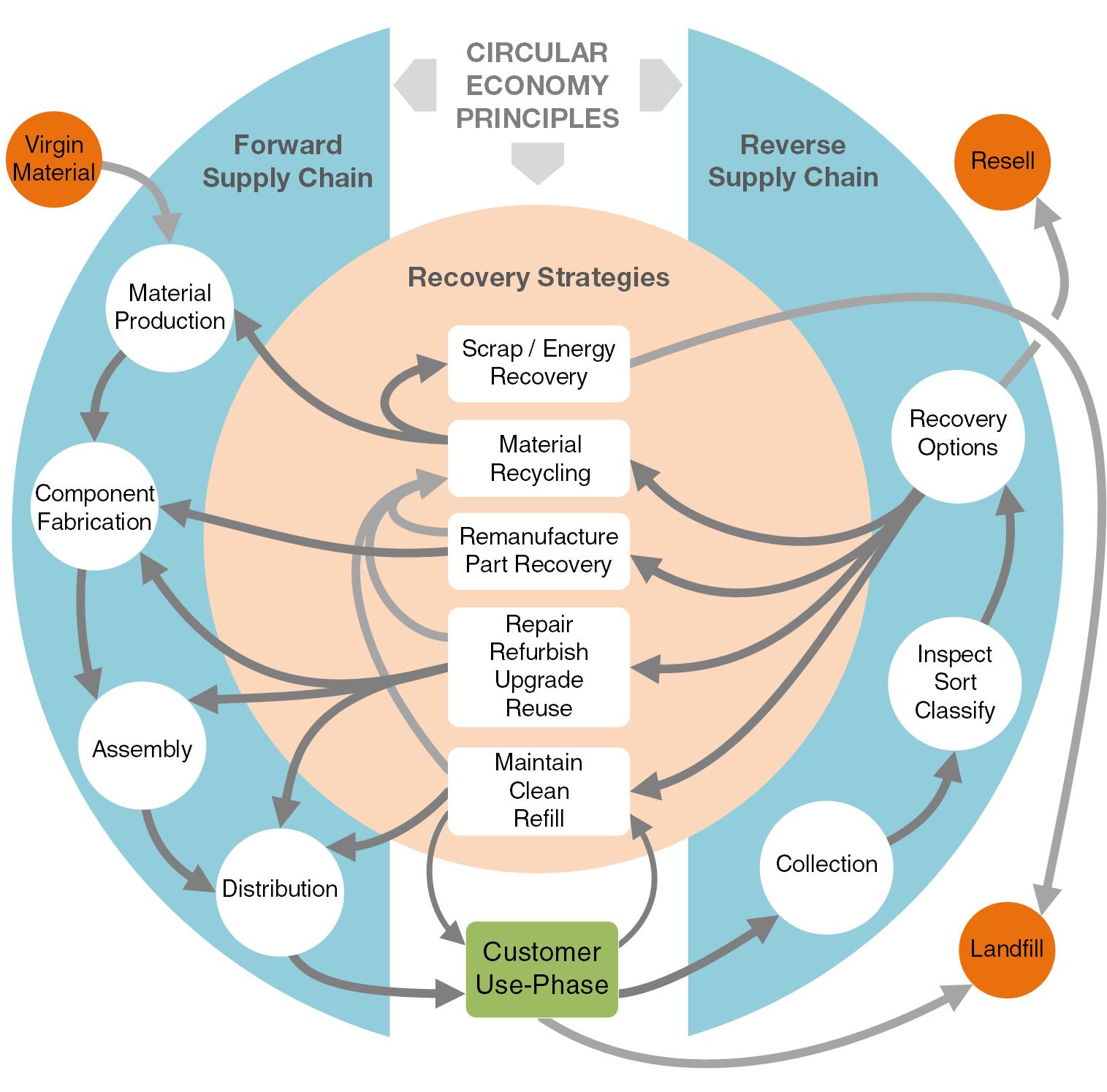

As David Denyer’s insightful article on organizational responses to crises suggests, adapting and innovating can and should be a part of managing a crisis and may be a way of ensuring we rise stronger, more robust, and resilient from the consequences of an event such as the corona-crisis. A circular economy, as opposed to today’s prominent linear economy of take-make-dispose, is an economic system based on business models that replace the concept of end-of-life waste by following principles such as reducing, alternatively reusing, recycling and recovering materials in production, distribution and consumption processes. By following these principles, a successful circular economy contributes to all the three dimensions of sustainable development. In this comment, I reflect on recent events and how they are supporting, reinstating, and challenging current beliefs and assumptions about the concept of a circular economy.

Circular supply chains are less risk-prone to extreme events

Although the corona-crisis has given us some entertaining online jokes about toilet paper, the crisis has also caused real-life misery, with supermarket altercations over the everyday essential. This is down to an assumed bullwhip effect within the supply chain. A global linear supply chain has long feedback loops and is vulnerable to local events spacially and timely distant to the end customers. As early as 1982, Walter R. Stahel has argued for the benefits of localized short supply-chains to reduce emissions caused by transportation and creating local employment. Having multiple, ideally local, product loops to reuse, repair, refurbish, or remanufacture products has been used as an argument to showcase the benefits of a circular economy to business as a means to reduce supply-chain risks caused by fluctuating resource prices and resource dependency from conflict regions and non-democratic countries. The current global situation supports the design of more local supply chains with products that have multiple life-cycles. Facilitating these strategies of reuse, repair, refurbish, or remanufacture to extend product life oftentimes requires changes in a company’s business model and shifting from selling goods to selling outcomes is often discussed as one solution to the challenge of reducing resource consumption.

Suggestion: Use circular economy principles not only to become more sustainable but to reduce your operational risk.

Questions: Do you have transparency upstream in your supply chain? Can you design supply-chains that close the loop and that are more resilient and robust?

Circular PSS Supply Chain (Widmer et al. 2018)

Contamination may be real

For twenty years, the idea that increasing the service component and shifting from Product- to Use- to Result-Oriented Product-Service systems has been discussed as a business strategy to increase revenue and reduce resource consumption. The assumption is that by sharing assets such as cars, facilities, and equipment, structural waste can be reduced, and the resources embedded in goods can be exploited more effectively. It is assumed, that by retaining ownership over products involved, a manufacturer or solution provider is incentivized to consider the total cost of ownership, designs products for longevity and recoverability, and maintains visibility during the use phase to predict maintenance, and optimise use.

The promising arguments for Product-Service Systems make them a fundamental building block in a circular economy but are not a panacea for achieving sustainability, and ‘everything-as-a-service’ is by far not risk-free. In consumer goods, the ‘contamination-effect’ describes a barrier to customer-acceptance as people, for example, are hesitant to wear clothes that have been used by others before. With a global pandemic spreading, the contamination is no longer a metaphor but reality, and a barrier that initially was regarded only to affect private consumers for psychological reasons may now very much apply to business customers well, as they may be literally contaminated. In our research, we explore the challenges manufacturing companies face when trying to increase their service level and circularity and identified the lack of customer acceptance as a critical barrier. Customers don’t want to give up ownership because they fear losing control over their operations. In light of the current situation, this is even more understandable as companies suffer from extreme restrictions to exchange with other market participants. The challenge for businesses is to develop solutions that integrate circular principles in a way that don’t require moving towards outcome-based contracting and leave enough control to customers, especially in times of crisis like we are experiencing currently.

Suggestion: Don’t count on moving to a ‘product as a service’ business model alone to become more circular, your customers may for legitimate reason not want it.

Questions: Can you add services to your product offerings to reduce resource consumption and pollution? Do you have enough control over the products and services you procure in times of a crisis?

Eight types of Product-Service Systems (Tukker 2004)

Circularity is an indicator of innovation

Managing competing goals is an enormous challenge but as well an everyday task in management and engineering. For many businesses, their goals have shifted overnight from creating profit to helping to prevent a global pandemic from spreading and damage limitation. Due to a lack of ventilators, a good number of manufacturers have announced that they will start producing these much-needed devices to treat severe cases of the illness. As a senior health official in a press conference pointed out, the most important thing in stopping a virus from spreading is response time and overthinking if your measures are too extreme is the enemy. In light of this, it is fair to assume that most of these manufacturers won’t consider end-of-life strategies for these ventilators or choice of circular materials. Whether it is the safety of a brake in a vehicle, the sterility of food processing equipment, or in this case the lead time of producing ventilators, safety and profit are king, and circularity nice to have. We base this statement on evidence from our research, in which we confirmed that circularity today comes at a price. For a manufacturing firm, human life always has priority over increased sustainability. For truly circular solutions, engineers, designers and managers have to consider all life-cycle stages, and environmental benefits must be proactively pursued and must not be regarded as beneficial spillovers. Product and service innovation is essential for many companies to create and sustain competitive advantage but measuring innovativeness is far from easy. Still, if companies succeed in designing truly circular products, it becomes a strong component in their value proposition, and may be just the tweak in their business model that aids successful recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.

Suggestion: Use circularity as an indicator for your innovativeness and communicate it to your stakeholders.

Questions: How do you measure innovation in your organisation? Can you identify product and service innovation that led to both an increase in customer value and reduction of resource consumption and pollution? Can you already identify where the weakest elements in your supply chains are?

Closing remarks

It is by no means the intention to ‘freeride’ on others suffering during this crisis by making a case for increasing circularity, nevertheless, it is hard to deny that many of the financial and societal consequences that we are currently and will be facing are caused by a vast dominance of linear global supply chains. I dare to argue that manufacturers and the global economy would have suffered less from the financial damage and restrictions on personal liberty if we already lived in a more circular economy. The benefits of more circular business models and operations are idiosyncratic to each company and navigating through the different principles and strategies is a challenge to managers in engineering, research, development, and marketing. Please leave a comment if you have examples of how circularity could or already does help your business, or if you want to learn more about a specific suggestion made.

References: