Why do some firms consistently outperform others? This has been a topic of research for many decades, ultimately polarising into two main research paradigms - the internal view and the external view – resulting in highly practical implications for businesses on how to make the most of their resources and capabilities.

Achieving a competitive advantage that can be sustained

One highly popular and well-known manifestation of the internal-vs-external view of the firm is the SWOT framework, which in essence leads managers to analyse the internal characteristics of the firm – its strengths and weaknesses – and in the same breath the external characteristics of the market in which the firm operates – the opportunities and threats. In order to achieve a competitive advantage, firms need to implement strategies that utilise their strengths and weaknesses to take advantage of market opportunities and to neutralise threats.

Taking a step back, let’s look at what competitive advantage is. According to Porter (1985), a competitive advantage originates from the ability to create value for customers that exceeds the costs of production and delivery. This is taken further by Barney (1991) who defines a competitive advantage as a value-creating strategy that is not being implemented by competitors. This competitive advantage, according to Barney, can only become a sustainable competitive advantage if the competition is unable to replicate the benefits of the strategy.

Looking inwards

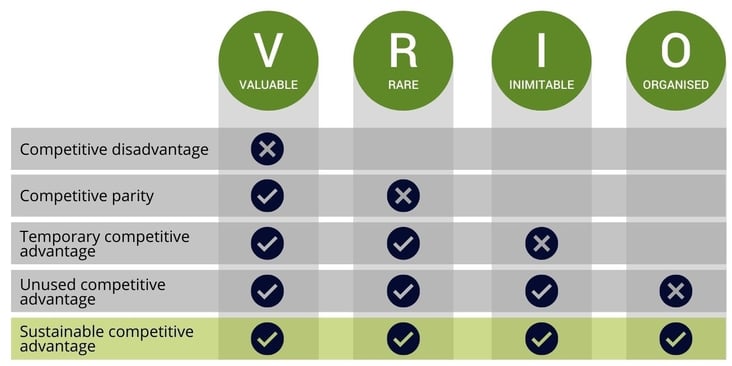

While some models of competitive advantage only take an external view – for instance Porter’s Five Forces – others turn their attention to the internal resources controlled by a firm, namely the resource-based view of the firm. This concept suggests that it is the internal resources that provide the source of sustainable competitive advantage and prescribes which characteristics such resources must possess in order to be considered of strategic relevance. These characteristics stem from what has been discussed earlier in this article – the creation of value and the inability of competing firms to replicate the benefits, translating into three categories: value (V), rarity (R) and inimitability (I).

The V, R and I characteristics in essence tell us that a resource, in order to contribute to achieving a sustainable competitive advantage, must deliver value, be rare and not be imitable by other firms either by direct imitation or substitution with another resource that produces the same outcome. A fourth characteristic that completes the framework is the organisation in place to be able to capture and capitalise on the given resource. That is, the resource may well be valuable, rare and inimitable, but if the firm is not organised to capitalise on the resource, then it will never materialise into a sustainable competitive advantage. It is not enough to possess the strategic resources, but firms have to be able to recognise them and understand how to utilise them.

Identifying strategic resources

A criticism of the VRIO framework is the lack of clarity on how to put it into practice. A good starting point is to analyse and identify value-creating resources within the business, to which end Porter’s value chain model can be helpful. This method helps us to break down our business processes and pick out individual resources that contribute to the firm’s value-creating strategy. But once those resources and capabilities have been identified, then what? Resource-based theorists talk extensively about what it means for a resource to be valuable, rare and inimitable, branching out into different research areas and taking advantage of a range of analytical frameworks to help clarify what VRIO means in practice. For instance, to be rare, a valuable resource must not be possessed by a large number of competing organisations and to be imperfectly imitable, certain criteria might apply such as social complexity, historical conditions, path-dependency or causal ambiguity.

This not only applies to individual resources, but also to combinations of resources, resource bundles. It could be that a resource by itself, such as an employee, is not VRIO alone, but combined with other non-VRIO resources, like a specific type of technology and the right reward structure, forms a resource bundle that can produce a sustainable competitive advantage. Such bundles can actually be more effective in sustaining that competitive advantage, as part of the inimitability characteristic may stem from social complexity that is difficult to reproduce, or the specific bundling of resources may be difficult to reverse-engineer from an external perspective.

In summary, understanding what it means for a resource to be valuable, rare and inimitable within the context of the business, and then how to organise the structure and processes to capitalise on it, are the critical first steps towards designing a strategy would ultimately lead to a sustainable competitive advantage.

References

Barney, J. (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management. 17(1), pp. 99-120.

Porter, M. (1985), Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance, The Free Press, New York.

About the Author

Violeta Da Rold is a Marketing Manager at Cranfield Executive Development, responsible for strategic marketing and international markets. She has previously worked in marketing for a technology firm and a communications agency, but originally comes from an architecture and design background. She is now in the final stages of an MSc in International Marketing Strategy, focusing on the resource-based view as a path towards sustainable competitive advantages in the Middle East market.